Singing in...

When you build a web application, everything is public. We've already grappled with this a bit before, when we started thinking about how bots might post data to our guessing game. By default, every page of our application is accessible to everyone. In addition, while in the last chapter we learned how we can differentiate sessions from each other, those sessions are thus far anonymous. We all know that this isn't the way most of our web interaction work - we are missing a fundamental aspect of web applications: Signing in!

Before diving into seeing how logins, sessions, accounts, and databases all interact to provide the sign in experience, let's cover some basic terminology:

-

Authentication: Checking to see if someone is who they say they are. Forms of authentication usually involve the user proving they have some sort of secret or information that only the real person would have. Examples are username/passwords, biometrics, physical access keys. By possessing the secret information, the user proves they are the account holder.

-

Authorization: Checking to see if the account is permitted to access/use a resource. Note, this is different from authentication. This is not about knowing whether the user is who they say they are - it's about whether the person can do what they are trying to do. The analogy here is that if you walk into a bank, you need to prove you are who you say you are to withdraw money from your account (authentication), but it doesn't matter who you are, you aren't allowed to go into the safe!

These two phrases are important, and unfortunately often used interchangeably. In fact, HTTP status codes actually got them wrong. When the status code standards were created, error code 401 was named Unauthorized, and 403 named Forbidden - where in reality, we used 401 for Unauthenticated and 403 for Unauthorized. It's a fact of life.

Most of the discussion in the chapter will be focused on the mechanics of authentication, because it involves the exchange of secrets. When done badly, exchanging secrets can cause a lot of problems beyond just your application. We will cover how to implement authorization as well, however authorization is much more of an application logic issue - checking to see who's logged in, and whether they have permission to do what they are trying to do. Authorization techniques vary from application to application, where there are very standard practices surrounding proper authentication.

HTTP Authentication

The HTTP protocol actually has a form of authentication built right into it. It's worth understanding, because there are some contexts where it is used - however it has some lacking. We'll point these out as we go, and eventually circle back to discuss some more after we cover encryption in the next section.

There are several type of HTTP Authentication, we'll cover the first - Basic in detail. The first step in implementing authentication is to write the web server such that it expects authentication for specific resources.

Let's hypothetically say your web application has two URLs that can be requested given GET request types: /public and /private. Any GET request to /public will receive an HTML response (status code 200). For requests to /private however, your web server logic inspects the HTTP headers, and will ONLY respond with the HTML (status code 200) if the Authorization header is successfully set. If it is not, then the server responds with an HTTP status code of 401, indicating that the resource cannot be accessed unless the user authenticates. Within the header of that response, the server will also set an HTTP response header - indicating the type of authentication required.

To summarize:

- Client sends HTTP GET request to

/private - Server sees there is no authentication, and responds with

401 Unauthorizedand anWWW-Authenticateheader set toBasic realm=something.

The WWW-Authenticate header tells the web browser (1) that the web server expects HTTP Basic Authentication, and (2) that the resource belongs to a specific realm. The realm is just a label, think of it as a zone or group of resources that your web application has, that need authentication. You might have just one realm, the entire application - or there might be different areas of your application that require specific or different authentication. In practice, you probably just have one realm (the entire application), and can name it whatever you want.

Pro Tip💡 The use of realm actually is an artifact of the mixin of authentication and authorization concepts that occurred back when HTTP was being created. In modern applications, you authenticate once, and authorization logic decides which areas of the application you are allowed to access.

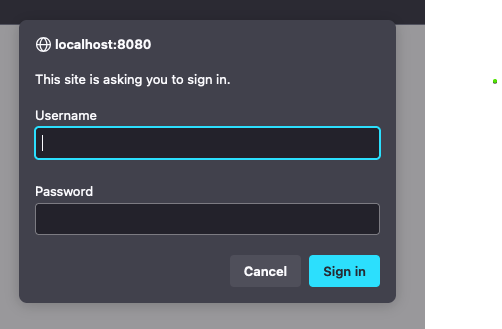

When the web browser receives the 401 response with WWW-Authenticate as Basic, it will present the user with a dialog. This dialog will contain language explaining that the user must authenticate. Some browsers will show the user the realm, others won't (most modern ones do not). Here's an example, where the Guessing game responds to all requests with WWW-Authenticate: Basic realm=guess on Firefox:

It's not pretty. More to come on this.

BTW, we achieved this simply by adding the following middleware to the app we keep developing. The middleware is attached to the app, not the router - thus it will effect every URL. As of now, there is no way of accessing any page, since we aren't implementing authentication - just requiring it!

app.use((req, res, next) => {

res.setHeader('WWW-Authenticate', 'Basic realm=guess');

res.status(401).send('Authentication required');

});

User Credentials

The browser is asking us for a username and password, so let's carry forward with this implementation. Instead of creating accounts on the guessing game, for now, let's hard code one specific username/password: username = guess and password = who. It's silly on purpose. We'll come back to account creation, password strength, etc in the coming sections.

We are temporarily going to break a cardinal rule in security and add these credentials right into the application code. We will never do this in practice, but as this section continues, you'll see that much of this code is merely for example currently.

In order to check for authentication, the web server can check for a request header. When the user types their username and password into the dialog box, the web browser automatically issues a new HTTP request with the Authorization header. Again, Authorization is really being misused here - it's authentication.

Authorization: Basic the-username-entered:the-password-entered

We can add the following code to do the check, and allow things to go through as normal if the user enters the guess/who combination:

app.use((req, res, next) => {

const authHeader = req.headers['authorization'];

if (authHeader) {

const credentials = authHeader.split(' ')[1];

const [username, password] = credentials.split(':');

if (username === 'guess' && password === 'who') {

return next();

}

}

res.setHeader('WWW-Authenticate', 'Basic realm=guess');

res.status(401).send('Authentication required');

});

That code is not complete or correct though - we are missing one thing. HTTP Basic Authentication dictates to the web browser that usernames and passwords should be encrypted. The browser does this with a simple Base64 encoding. Instead of sending Basic guess:who, it instead sends Basic Z3Vlc3M6d2hv. Base64 encoding is a common thing though, which we can decode in Node.js pretty easily:

app.use((req, res, next) => {

const authHeader = req.headers['authorization'];

if (authHeader) {

const base64Credentials = authHeader.split(' ')[1];

const credentials = Buffer.from(base64Credentials, 'base64').toString('ascii');

const [username, password] = credentials.split(':');

if (username === 'guess' && password === 'who') {

return next();

}

}

res.setHeader('WWW-Authenticate', 'Basic realm=guess');

res.status(401).send('Authentication required');

});

With this in place, we actually now have a fully functioning app that requires (an albeit simplistic) authentication process. The browser has taken care of most of it for us. The browser will continue to send the Authorization header for a period of time, with every request - just like it sends cookies - it's the same idea. Eventually, the browser will ask the user to re-enter their credentials. It's a really straightforward implementation - it's basic.

So - let's top here for a moment and consider a two really big problems though.

-

The "encryption": The encryption involved with HTTP Basic Authentication is not in any way effective. Literally anyone can decode the username/password, if they managed to view the HTTP request in it's raw form. This brings us to our first major obstacle for HTTP Authentication: it's fundamentally broken if you aren't using HTTPS. When HTTP requests are sent in plain text, then usernames and passwords are too. This is a show stopper. We cannot use HTTP Basic Authentication with a normal HTTP connection, as transmitting the user's password over HTTP is irresponsible. It can be captured by all manner of man-in-the-middle (MiTM) attacks.

-

The UX: A second problem (not necessarily a show stopper) is the user experience. The dialog box the browser displays to the user is ugly. It's simplistic - it doesn't have any way of providing a sign up or create account link. It doesn't have any branding or styling. It doesn't have any nice password hints and guidance. You might like the purity of it all, but most people want and expect something nicer. With HTTP Basic Authentication, we are sort of stuck with this though- there are some ways around it, but they are painful.

Alas, HTTP Basic authentication was built into the web during a time when it was hard to see where the web was headed. Most didn't envision a fancy login screen, nor the importance of doing anything more than simplistic obfuscation of passwords. We know a lot better today, of course.

Let's see how we can approach fixing problem #1. First, it's important to understand that basic means basic, and there are more ways we can leverage the standard HTTP authentication mechanics to make it more secure. You can read more on the MDN - but at the end of the day, anything we send in plain text can be intercepted. This means that to attack problem #1, we need to stop sending things in plain text. This means we need to dive into TLS and HTTPS - and then we can circle back to deal with the rest of the issues surrounding HTTP authentication.