Why Callbacks?

One of the hardest concepts for most students to grasp starting out with JavaScript is the callback function. We learned about it when we saw a few of our very first JavaScript programs - the networking examples in Chapter 2. Given callback were present in such early examples, it shouldn't be shocking to learn that callback are related to JavaScript in a deeply fundamental way.

Let's refresh with an example we've already seen:

const http = require('http');

const handle_request = (req, res) => {

// Interpret the request, build

// and send a response

}

const server = http.createServer(handle_request);

server.listen(8080, 'localhost');

The above example is how we write HTTP server code. We define a function, and then tell the http server instance we created to call it, whenever an HTTP request arrives on the underlying network socket. handle_request is a callback function.

Take some time to think about the following:

- When will that function get called?

- How many times will that function get called?

- Can that function get called twice, at the same time?

The answer to #1 is... who knows!. The server (which is where this code is running) doesn't control when an HTTP request is received. That depends on when a web browser, on a computer potentially across the globe, creates such a request! We know the handle_request function gets called if and when an HTTP request is received, but we have absolutely no way of knowing if and when such a request will be received.

Could we instead have a function to just wait for a request, and return a corresponding object (containing the parsed request, and a ready-to-use response object)?

const rr = httpServer.waitForRequest();

handle_request(rr.req, rr.res)

This seems more deterministic, and more natural to someone who is more accustomed to programming in other languages. The code implies (by the function name) that we want to wait for an incoming request, and then once it arrives we want to process it. Notice that we still don't know how long we will wait. It's the same situation, it's just written differently. It does seem a little easier to think about, since it's a linear style of programming.

On to question 2 - how many times will it be called? Again, we can't answer this question. We may receive one request, we could receive ten thousand requests. We might even receive zero requests. The code we started with isn't concerned - it's just telling server that whenever, and every time a request is received, call handle_request.

To do the same with our hypothetical waitForRequest function, we'd need some sort of loop:

while (true) {

const rr = server.waitForRequest();

handle_request(rr.req, rr.res);

}

The loop above is explicitly waiting and processing, in sequence, over and over again. It's important that you keep thinking back to the callback example at the beginning of this section - it's doing the same things, the difference is that the loop isn't in your code, it's somewhere else! Let that sink in - they are the same, it's just that you've passed handle_request to the server object, and somewhere in the server object's code, there's a loop that is calling it!

Now what about question 3 - will we receive two requests at the same time? The answer is... maybe. We can't control whether two people click a button on their phone at the same time, and generate two HTTP requests to our web server at the same time. It's just luck.

Taking the looping example above, where we call waitForRequest then handle_request, what happens when handle_request is called? It takes some amount of time to do the request processing and generating the response. How much time? Hard to say. Let's take it to an extreme, and say it takes one second. What happens when we receive a second request during the time we are processing the first?

This gets us to the core of the problem. By definition, in the looping code, we are either waiting for a request or we are handling a request. If a request comes in while we are handling another, what happens to the request? There are two possibilities:

- The incoming request is queued by some other process

- The incoming request is dropped.

Option 1 seems way better, but in order for that to happen, it means some other process (program) on your computer is reading the incoming network bytes, and is willing to hold on to them until you decide to "wait" for another request - at which point it hands it over to you.

In reality, there is a program doing this already - it's your operating system. It will cache some network traffic - but not much. Making matters more difficult is that each time more requests arrive while you are processing the previous ones, you will fall further and further behind. A queue of incoming requests will build, and eventually the operating system will begin dropping the network traffic. Worse yet, clients will stop waiting, and abandon the request.

The solution is to build your own queue, and figure out a way to process things "faster", usually by processing multiple requests in parallel. Without getting into too much detail, we end up with something like this:

// Will continue to receive http requests, and

// put each on a queue. This happens in a new thread

server.start_receiving();

while (true) {

// Blocks until there is a request in the queue

const rr = server.next();

// Handles the request in a new thread, allowing

// the loop to return to the top immediately.

new Thread(handle_request(rr.req, rr.res))'

}

If you aren't familiar with multithreaded code, this might seem complex. If you are familiar with multithreaded code, this should seem complex. Multithreaded code allows the programmer to execute sequences of code in parallel, with each sequence running independently of each other. They don't wait for each other. This makes it easier to do things faster, especially on machines with multiple CPUs. It also makes things harder to program - issues like race conditions and synchronization abound. Creating new threads for each request can pay off, but it doesn't come for free either. The operating system is required to create new threads, and that means we must make API calls to it - incurring additional time.

What is being described above is dispatch. Dispatch is a situation where we are receiving incoming jobs, and each job is being independently handled by independent code. There is logic required to queue incoming jobs and dispatch the jobs to appropriate code. It's a simple concept, that becomes complex when dealing with high volume and performance requirements. Webservers need to handle high volume, and users expect performance.

This is a huge topic, we could spend several chapters discussing the ins and outs of multithreaded programming. The goal here however is to motivate why callback functions exist. Callback functions are an elegant encoding of the dispatch problem.

const handle_request = (req, res) => {

// Intepret the request, build

// and send a response

}

const server = http.createServer(handle_request);

server.listen(8080, 'localhost');

The code above is doing dispatch, but dispatch is happening within server, not our own code. We are simply saying - use handle_request when you dispatch a request. We are giving server the function to call in the loop, but we are letting server deal with the loop itself.

Multiple Streams

There's a secondary benefit to handling the dispatch problem with callbacks rather than a dedicated loop. Let's create a new more abstract example. Suppose you have two sources of incoming jobs (A and B). Each time a job is received, the job must be dispatched to a separate handler - based on the type of job that is received - handle_a, handle_b. You don't know when the jobs will arrive, and you can't assume they will arrive in any particular order. You may receive five jobs of type A before ever receiving a job of type B.

How can we replicate our dedicated loop?

We can't have two loops, because we need to be able to handle a mix of incoming jobs. We can't handle all the A jobs before B jobs!

// This won't work! We never leave

// the first loop!

while (true) {

const a = server.waitForA();

handle_a(a);

}

while (true) {

const b = server.waitForB();

handle_b(b);

}

We'd instead need to do something like this:

while (true) {

const a_or_b = server.waitForA_or_B();

if (a_or_b is a)

handle_a(a_or_b.a);

else

handle_b(a_or_b.);

}

Pretty awkward. Now what if we have 5 different job types, with 5 different job sources? We'd have to have all sorts of combinations of waitFor functions, and then big branches in our loop to figure out which event we need to process.

This is where callbacks start to really shine:

const handle_a = (a) => {

// ...

}

const handle_b = (a) => {

// ...

}

server.onA(handle_a);

server.onB(handle_b);

Notice how that scales. It's because the loop structure and the dispatch is within server. It's written once - with all the necessary complexity and care - and now the programmer may leverage all that work by simply registering callback functions. handle_a and handle_b could be called thousands of times. If we have more jobs types, we simply create more handlers.

The examples above are fairly abstract. If you are newer to programming, it might be enough depth for you, for now. If you have more experience, especially in any sort of systems programming, you might be wondering how this is all actually happening - as we've glossed over some things in the abstract examples.

What is I/O, really?

When you create a program, you have a sense that your code will be executed at some point, on a machine. That machine has an operating system, and the operating system is responsible for launching this program you've written - at a user's request. You also have a sense that your program isn't the only program running on the machine. You know, just from using a computer, that there are many programs running that appear to be doing so simultaneously. This concept is called timesharing, and it is up to the operating system to maintain the illusion (in the case of single CPU systems) of multi-tasking. In reality, each program running on the computer gets a small time slice to run on the CPU, before the operating system chooses another program to run, for a similarly small slice of time. Programs are run according to a scheduler, and run for small enough time intervals that to a human being, it gives the appearance that all are running - in much the same way a video fools a viewer into thinking they aren't just seeing a sequence of images being swapped rapidly.

How does your program, that is running on the CPU, get pulled off the CPU though? Most students who haven't studied operating systems have a knee-jerk response: the operating system does this. This really isn't accurate - because remember, the operating system is just a program too. In a single CPU system, if your program is running, then by definition the operating system is not - and thus cannot "kick" a program off the CPU!

The reality is that programs exit the CPU for one of four reasons:

- The program voluntarily yields the CPU to allow other programs to run. This happens when the programmer decides to add an API call into their code that explicitly asks invokes the operating system. This doesn't happen often.

- The program exits. This might be due to error, or natural exit. While mostly every program eventually does this, it's rare in the larger picture. We are thinking about time sharing, where programs are moving on and off of the CPU thousands of times per second. Most programs won't exit within that time period.

- A CPU timer expires, allowing the OS to run it's scheduler. CPU's have hardware timers that will interrupt the CPU and shift execution to the operating system. The operating system sets these timers before choosing the next program to run. This effectively puts a maximum cap on the total time the program can own the CPU without the operating system running.

- The program invokes an I/O call. All I/O calls result in the operating system running - and performing I/O on the user program's behalf.

Number 4, I/O calls, is the most interesting for our purposes. A computer consists of many devices - the CPU being one of them. The CPU does computation, the add, multiply, subtract, etc. operations of a program. Other devices, such as disk, network, display, mouse and keyboard are part of the system too however - and they are generally referred to as input and output devices - IO devices. Really, all devices other than the CPU are considered I/O devices.

A principle job of the operating system is to make efficient use of all the devices of the system. Each device takes time to perform it's operations. Some devices are fairly quick, some are extraordinarily slow. Some devices depend on humans (ie, waiting for keyboard input), which means slow doesn't even begin to do justice to how much slower they are than CPU operations.

No user program (any program that is not the operating system) is permitted direct access to devices. There are many reasons for this - but the two main reasons are fairness and safety. We don't want processes to consume all the devices on the system, and we don't want processes (programs) to use devices inappropriately. Therefore, all device access is achieved by making API calls - usually referred to as system calls. Operating systems provide C APIs to perform all sorts of operations - file access, network communication, display, etc.

Critically, when a system call is invoked, the caller (the user program) is removed from the CPU and the operating system begins running. The operating system must then initiate the operation it has been requested to perform by sending a signal the given device. Keep in mind, once the signal (an instruction, sent from the CPU, over the bus, to the intended device) is sent, it will take time before the device begins to operate, and before it completes. This time might be a few hundred milliseconds, but normally we measure this time in clock cycles - or CPU clock cycles. One clock cycle is one instruction that the CPU executes. Reading from a hard disk may take hundreds of clock cycles - however the work being done is not done by the CPU, it is done by the hard disk's microcontroller. This is a key concept - the operating system, is a program, running on the CPU. One of the instructions that it executes on the CPU is a command to send a signal to a device. The operating system will now have nothing useful to do until the device completes the operation.

It has two options:

- Do nothing (it can literally execute a no-op on the CPU, an instruction that does absolutely nothing)

- Allow another program to run. Note, this will not be the program that asked for the device operation to be performed, since that program is necessarily waiting for that operation to be completed!

The choice should be obvious - since there is nothing useful for the operating system to do on the CPU, and the program which asked for the I/O has nothing to do either, it makes sense that another program is chosen to run. At some point in the future, the initiated I/O will complete, and the device will generate a hardware interrupt to invoke the operating system (this is actually the *fifth way a program leaves the CPU - on I/O completion). The operating system will examine the results, and schedule the initiating program to run - and the results are passed to it.

I/O and Operating System APIs are a huge part of computer science and systems programming. We won't go much deeper in this book, but take a look at these references if you are interested:

Blocking Model

The discussion above on I/O is a difficult concept. There was a lot going on. What does all of that actually look like though in code?

int x = 5;

printf("%d\n", x);

Yes - that really is it. That code prints an integer to the terminal. The code is simple. However, here's what actually happened within the printf call:

- The C code executed a trap command on the CPU, with parameters to invoke the operating system.

- The operating system began to run, and computed pixels within a frame buffer (representing the terminal's window) corresponding to the number 5. Those pixels needed to be flushed to the output device, so a signal was invoked to the graphics device.

- While the graphic device did it's work (this is an oversimplification!), the OS handed the CPU off to another program which likely ended up making an I/O call - repeating this entire process several times. Many things can be happening during this time, but there is one thing we are sure isn't happening: our program (the one that called

printfis not running). - Eventually, the graphics device subsystem confirmed the pixels had been flushed to the actual screen. The operating system regained the CPU after the graphics device interrupted the CPU.

- The operating system added the original program (the one that called

printf) to the list of programs ready to run again, and eventually it gets selected. - The line of code after the

printfbegins executing.

This is called a blocking call. Blocking calls, invoked by a user program, result in the program blocking - or being taken out of the list of schedulable processes, until the result of the blocking call is available. From a programmer's perspective, it's a vary simple model. It hides much complexity.

Pro Tip💡 Understanding blocking calls is the most critical part of this section. A blocking call results in your program being suspended, while the operating system and the devices on the computer do their work. By definition, your program is not running - and will not run until all the work is complete. While your program is blocked, other programs may run - which is a good thing from a global perspective. However, remember - when your program is blocked, it can't do anything else. It can't respond to user input. It can't draw anything to the screen. It can't receive network events. It can't do any computation of any kind. It is not running.

The printf function is quick, and so it might be difficult for you to conceptualize the full story here. So, let's create another hypothetical example:

Suppose you have a program that draws things on the screen, and responds to mouse events (mouse movement, clicks, etc). When the user interacts with the program, the screen is redrawn to indicate the results of that interaction. In addition, sometimes your program needs to read data from disk, perhaps several hundred MB - which can take a few seconds. Now let's suppose your application has the following general structure in it's code:

while (true) {

data = null;

mouse_events = read_mouse_events();

if (mouse_events.must_read_file) {

// This blocks, and can take several seconds

data = read_file(filename);

}

draw_screen(mouse_events, data);

}

The loop above is an abstract example with some hypothetical functions, but you can appreciate what's happening here. The program sits in a loop, gathers user input, and draws the results to the screen - over and over again. Theoretically, it should be able to do this thousands of times per second, which gives the user immediate feedback. For example, as they move their mouse around the screen, the mouse cursor can be drawn immediately - providing the impression that it smoothly traveling around the screen.

If the user does something such that must_read_file is true however, now the code must actually ask the operating system for file data. If this is a blocking call, then we have a big problem. While read_file is executing, which could be many seconds, we are blocked. draw_screen cannot be called, and we can't read_mouse_events either. The user may continue to move their mouse around, but the cursor won't redraw. They may try to click buttons, menus, and move scroll bars - but the screen isn't going to redraw. Our program is blocked.

You've probably encountered programs that behave like this actually. It's not uncommon. The problem can be solved however, and traditionally it was solved with multithreaded code. A thread is a separate path of execution. When a program has two threads, each thread is schedulable. If one thread is blocked, the other thread can still run on the CPU - they are independent of each other. Let's look at how this solves the problem.

// THREAD 1 - User input/feedback

// Shared with Thread 2

data = null;

while (true) {

mouse_events = read_mouse_events();

if (mouse_events.must_read_file) {

signal_file_thread();

}

draw_screen(mouse_events, data);

}

The user dispatch thread reads mouse inputs and draws the screen. If the user takes an action that requires a file to be read, that is detected - but instead of actually reading the file, we send a signal to the second thread. Note, we're hiding complexity here (ie how is this signal sent?) in an effort to keep this fairly high level, because we won't be doing multithreaded code in this book.

So, at the same time, there is another thread waiting for this signal.

// THREAD 2 - File Reading

// Shared with Thread 1

data = null;

while (true) {

wait_for_signal();

data = read_file(filename);

}

The second thread simply waits for signals from the first. When told to do so, it calls read_file - which is still a blocking call. Crucially, while Thread 2 is blocked, Thread 1 is happily continuing - responding to user input and drawing to the screen. This is how multithreading solves the problem - it moves the blocking calls to separate threads, so the thread handling user input and drawing (or whatever work there is to be done) is not blocked.

Non-Blocking Model

The majority of programming languages use blocking calls to perform I/O activity. This is largely because in most cases it is OK to do so, and is easy to code. When it's not OK to block, then programmers must use multi-threaded code - which substantially increases complexity.

Node.js is designed differently. In Node.js, the majority of I/O calls (and even some CPU intensive calls) are designed to be asynchronous and non-blocking. There are a few reasons for this:

- Node.js was built with I/O intensive applications in mind, and I/O intensive applications tends to suffer when I/O calls are blocking

- JavaScript non-blocking API's easier to design, since it's much easier to work with callback functions than in other languages (at least, at the time of Node.js's creation).

Before reviewing how Node.js code would be written for the examples above, let's discuss a bit more about it's architecture. Node.js is a C++ program. It's the runtime for JavaScript. It has two fundamental parts - (1) V8 JavaScript Execution Engine and (2) Operating System interface code - to give JavaScript access to the filesystem, network, input/output devices. We've discussed V8, the critical part is (2) right now. Node.js provides a JavaScript interface to the C / C++ APIs the operating system supports. This allows your JavaScript code to invoke the same system calls as a C and C++ program would make - but in a JavaScript style.

Since Node.js is the runtime program for your JavaScript code (when writing server-side code in this book), and it is providing access to the operating system's system calls - it has full control over how your JavaScript code can interact with those system calls! It can choose whether to make those operations blocking or non-blocking, and it chose non-blocking.

Nearly all of Node.js's I/O calls expect the caller to provide a callback function. When the Node.js I/O call is invoked, it asks the operating system to start the I/O call, but importantly it does this in a non-blocking manner - the operating system does not suspend Node.js until the I/O call is completed. Node.js then immediately continues executing the JavaScript code that made the I/O call.

Read that sentence again. When you make an I/O call in Node.js, the call returns immediately. Before the I/O call is completed.

When the operating system finally receives notification that the I/O has been completed, Node.js will likewise be signaled. Node.js will continue executing whatever JavaScript code is currently running (more on this in a moment), and once it has nothing to run, it will check for I/O completions. Seeing the I/O has been completed, Node.js then calls the callback function that was provided earlier.

So, let's see how this works in practice, using the same hypothetical program as above.

let data = null;

const process_mouse_events = (mouse_events) => {

if (mouse_events.must_read_file) {

// read_file returns IMMEDIATELY

read_file(filename, (file_data) => {

// Callback function, sets the data

// variable

data = file_data;

draw_screen(null, data);

});

}

draw_screen(mouse_events, data);

}

read_mouse_events(process_mouse_events);

These aren't real Node.js functions of course, but they are written in the style of Node.js I/O calls. Notice that read_mouse_events is now non-blocking. Only when a mouse event is ready does the callback function process_mouse_events get called. Presumably, inside read_mouse_events, there is some mechanism that continue to poll for input over and over again - so process_mouse_events is called for all mouse events.

Inside process_mouse_events, we may invoke read_file, but now read_file accepts a callback. read_file does not wait for the data to be read from disk, it returns right away. The screen can be drawn right away as well.

When the data does arrive, the callback is invoked, and data is set. Since it is assumed that the data that is read in some way alters what should be drawn, we call draw_screen again. This time, we provided null as the mouse parameter, since the call is not invoked as a direct result of mouse data at all.

There's no question - this is harder to understand than the original blocking code. It's likely no harder than the multi-threaded code, and in fact - it's a lot safer, as we do not need to worry about synchronization, shared memory, etc.

Pitfall: Clogging up the "Event Loop"

The JavaScript code above hides something, something that is within Node.js and is driving everything we do. It's called the Event Loop.

Think of Node.js as a C++ program that does the same sort of loop that we started out this section with - waiting for various events. One of the events that it waits for is the availability of code to execute. The following (incredibly simplified) pseudocode illustrates what Node.js is doing:

let code_queue = new Queue()

let pending_io = new List();

// Start the program

code = get_entry_point();

code_queue.push(code);

while (!code_queue.empty() && !pending_io.empty()) {

code = code_queue.next();

if (code) {

// Runs code, and if it hits an I/O call,

// starts the I/O, returns record (id, callback).

// If no I/O call is made, keeps running until

// the code itself completes and returns null.

io_invoked = run(code);

for(const io of io_invoked) {

pending_io.push(io);

}

}

id = operating_system.is_anything_ready();

if (id) {

// Looks up the id in pending_io, and if found, and

// and has a callback function, adds the callback function

// to the code queue.

io = lookup_pending_io(id);

if (io && io.callback) {

code_queue.push(io.callback);

}

}

}

When your JavaScript program starts, the globally executable JavaScript (the program entry point) is added to the code_queue, and drops into the main event loop. The event loop will continue to run until there is no additional code to run, and there are no pending I/O calls. If you follow along, the most critical part to understand is the run function. It accepts JavaScript code, and runs it to completion. While running it, the code may make I/O calls. Each I/O call gets an identifier and a possible callback. When the code is complete, those I/O calls and callbacks are added to the pending IO queue. Before taking the next chunk of code, we check to see if any I/O has completed - and if so, we place that I/O call's callback on the code queue.

Now, let's see how we can effectively kill Node.js's ability to process I/O, by monopolizing the event loop.

let data = null;

const process_mouse_events = (mouse_events) => {

if (mouse_events.must_read_file) {

read_file(filename, (file_data) => {

data = file_data;

draw_screen(null, data);

});

}

// Infinite loop

while (true) {

foo();

}

draw_screen(mouse_events, data);

}

read_mouse_events(process_mouse_events);

In the code above, when we receive a mouse input, we check to see if we must read a file. Let's say we do - and we invoke read_file. We know that when read_file completes, Node.js will call the callback we provided - which sets the data variable. However, after calling read_file we drop into an infinite loop. This code will never complete. If you look at the pseudocode for the event loop above, we are inside the run function - and that run function will now never return. Node.js will never get to check to see if read_file has completed, or check to see if there are any more mouse events. Your program is unresponsive.

The example above is an extreme example. Instead of having an infinite loop calling foo, maybe instead you just do some number crunching - for a few seconds. This is still problematic, because you are still blocking the event loop. While you are doing your number crunching, you are not allowing Node.js to check for I/O completions. Some times this is simply unavoidable - but it's important to understand the effects. Anytime you do something CPU intensive, without an I/O blocking call, you are blocking the event loop.

More Reading

Node.js implements system calls in conjunction with another C++ library embedded within it's source code - libuv. While you don't need to understand all the details of how Node.js is implemented in order to write web servers in Node.js, the information and background knowledge is certainly helpful.

- Node.js Event loop explanation

- Node.js blocking and non-blocking explanation

- Node.js callback pattern explanation

- libuv

Real-World - HTTP Request Bodies

Let's drill down to something more concrete, and related to our core focus - web development.

We saw in the last chapter how HTTP request bodies were handled by the http library. Instead of simply adding it to the req object, like it does with query strings, it is instead the programmers responsibility to handle data and end events on the request, and then parse the request body themselves. Why is this?

Recall, HTTP request bodies can be large. There's no technical limit, and in practice, a web client (browser) could send an entire movie file, of several GBs over the network - to upload a video to a server. This will take minutes. The http library needs to work reasonably for all use cases, and if it were to block until the HTTP request body was fully received, it would end up stalling our ability to process any other requests that come in while we are reading GBs of data from one particular web browser! Instead, the http implementation chunks the data, reading a bit off the socket at a time, and invoking our supplied callback.

const handle_request = (req, res) => {

let body = "";

req.on('data', (chunk) => {

body += chunk;

});

req.on('end', () => {

req.form_data = qs.parse(body);

serve_page(req, res);

});

}

http.createServer(handle_request).listen(8080);

When a request arrives, we immediately register a callback function for each time a data chunk arrives. The req.on function returns immediately, and we call it again to register a callback for the end event. That call to on returns immediately too, and thus handle_request returns immediately. At that time, we are free to handle new requests (new calls to handle_request) while the network device continues to receive chunks associated with the first HTTP request. Each time a chunk arrives, we append it to the body variable, which is held in scope since active callback functions (the ones associated with data and end) have captured them within their scope (closures). The append is quick, so the callback for data returns quickly, and isn't tying up the event loop. Between chunks, the entire program is free to do other things. Additional HTTP requests may come in from other clients, and we can happily process them. When end is invoked, we then are ready to parse things - in our use case above it's just form data.

Pro Tip💡 When writing web server code, you always need to remember that new HTTP requests can be arriving at any time, because you are potentially serving thousands (or millions!) of web browsers simultaneously. You always have something else to do, while I/O calls are being performed. Never forget this!

Reusing the Request Body Parsing

It's a pain to keep writing all that code to parse request bodies. You might be tempted to do the following:

const parse_body = (req) => {

let body = "";

req.on('data', (chunk) => {

body += chunk;

});

req.on('end', () => {

form_data = qs.parse(body);

return form_data;

});

// ?

}

const handle_request = (req, res) => {

req.form_data = parse_body(req);

serve_page(req, res);

}

http.createServer(handle_request).listen(8080);

That code might seem nice - since we could imagine reusing the parse_body function in other areas of our web server, or in other projects. That code is fundamentally broken though, and WILL NOT work.

Pro Tip💡 Pay attention to why the code above doesn't work - it's one of the most common mistakes students make!

The parse_body function above registers callback functions on the req object just fine. In fact, each time a chunk of data is received, or the end of the request body is found, those callbacks do get called. The problem is that handle_request is long gone. Let's see why:

When parse_body calls req.on('data', ..., that function returns immediately - it's simply registering a callback. The same thing occurs when req.on('end', ... is called - the callback is registered and then the function returns right away. At that point, we arrive at the line of code marked with the comment - // ?. At this time, no chunks have been processed, and the form data has not been parsed. We've reached the end of the parse_body function, and it returns. The handle_request function expected the result of parse_body to be something, but it's not - it's just undefined. handle_request serves the page, with no form data at all.

BTW, remember, we couldn't have done return body from parse_body, or attempted to parse the body at the // ? line, because the data hasn't been ready yet.

So, how do we fix this? How do we wrap up the callbacks associated with parsing the request body so it's reusable? The answer isn't quite as satisfying as we'd like, yet. For now, the best we can do is wrap it up using another callback.

// The second parameter (done)is a FUNCTION, a callback

// that the caller wants parse_body to call when the

// body has been parsed.

const parse_body = (req, done) => {

let body = "";

req.on('data', (chunk) => {

body += chunk;

});

req.on('end', () => {

form_data = qs.parse(body);

// Call the function we were provided, with

// the parsed form data

done(form_data)

});

}

const handle_request = (req, res) => {

parse_body(req, (data) => {

req.form_data = data;

serve_page(req, res);

})

}

http.createServer(handle_request).listen(8080);

The parse_body function above has been changed, so it accepts a callback function. This is the first time we've used callbacks ourselves - and it might really help you conceptualize how this all works! The parse_body function still returns immediately, so handle_request also is returning immediately - but it's returning without actually sending the page to the browser. It has however passed a callback to parse_body, as it's done parameter. That callback receives the parsed request body, adds it to the req object, and serves the page. parse_body calls done (which is the anonymous function passed into it from handle_request) once it receives the end event and has parsed the data.

Events vs Results

Before moving on, it's worth considering that we've actually been seeing two different types of callback use cases.

const parse_body = (req, done) => {

let body = "";

req.on('data', (chunk) => {

body += chunk;

});

req.on('end', () => {

form_data = qs.parse(body);

done(form_data)

});

}

The req.on function is used twice in the code above. Once for data, and once for end. Note though, we sort of implicitly accept that the data event might fire many times, while we understand end will only be called once. Likewise, we saw the read_mouse_events function in examples above, which was presumably allowing us to register a callback for mouse events - and we understand that there will be many mouse events. We also saw read_file, which accepted a callback with the data read from disk - and we understand that that callback would be called once, when the file data was available.

There are two situations, both of which are handled with callback functions:

- streams of events, where a given callback is called whenever an event arrives.

- results of I/O calls, where one call results in one callback invocation.

These two use cases are not mutually exclusive. For example, we might have a stream of events, and only receive one event. The end event is a good example of this - it's nature and name imply it only happens once, but if you look at the code - it's written like any other event (like the data event). The two use cases are used fluidly, and you should be thoughtful when working with callbacks because of this. You should always ask yourself - how many times would my callback be called?. The answer is usually found from the context, and the documentation. There is not hard and fast rule!

There are some considerations regarding streams of events vs results. When dealing with streams of events, we are essentially creating an entry point - a place where are program will begin executing whenever an event occurs.

const ke = (key) => {

console.log(key);

}

keyboard_events(ke);

In the code above, it's very clear - we'll have more than one keyboard event. The hypothetical (not real!) functions keyboard_events is accepting a callback to call whenever a key is typed. The ke function is an entry point - it executes and operates only on it's input - the key pressed. Each time it is called, the execution of the function (the console.log) is called - without regard to any other key that has been or will be pressed. Each invocation of key is independent.

Contrast this with the code that performs some operation on the result of an asynchronous call:

const handle_file = (file_data) => {

// do something with file data.

}

read_file(filename, handle_file);

The code above, if you replace the names, looks almost identical as the keyboard code - with one exception - read_file accepts a filename as input. The keyboard_events function didn't accept anything but a callback, because it invokes the callback for every key. This difference does not imply any conceptual difference though - we could have just as easily imagined a function that registered a callback to a specific key.

The point is, you can't necessarily tell if we are dealing with a stream of events that can happen at any time, or we are looking for a specific result from an asynchronous operation. The different depends on context, not code structure.

Callback Patterns and Anti-Patterns

Callbacks are OK, and we get tremendous benefits from them when used well. However, they do come with some usability problems. Each of our examples so far have involved calling one callback function in a sequence. Most of the examples registered a callback for an event or result, and then when the callback was invoked, we were able to finish whatever work we wanted to do.

What happens if we need to do some work, but before we can do that work we need the results of two asynchronous I/O calls though? Let's say, we want to read two files, and append them together. By the way, instead of using read_file, let's actually just use the real Node.js function - readFile. The readFile function is found in the fs module, and accepts three parameters: (1) the filename, (2) the file encoding, and (3) a callback to receive the data. The callback follows a conventional pattern that most Nodejs callbacks follow - the first parameter is for an error (and many be null) and the second is the actual result.

First lets' read ONE file:

const fs = require('fs');

fs.readFile('file-1.txt', 'utf8', (err, data) => {

if (err) {

console.error(err);

return;

}

console.log(data);

});

OK, so inside the callback we have the file data. How do we get the second file? We could now call readFile again:

const fs = require('fs');

fs.readFile('file-1.txt', 'utf8', (err, data) => {

if (err) {

console.error(err);

return;

}

console.log(data);

fs.readFile('file-2.txt', 'utf8', (err, data) => {

if (err) {

console.error(err);

return;

}

console.log(data);

});

});

This seems messy. We did a pretty poor job of naming variables, reusing "data". Let's clean it up a little, and pretend we have an append function that can merge the two file data variables together.

const fs = require('fs');

fs.readFile('file-1.txt', 'utf8', (err, f1) => {

if (err) {

console.error(err);

return;

}

fs.readFile('file-2.txt', 'utf8', (err, f2) => {

if (err) {

console.error(err);

return;

}

combined = append(f1, f2);

});

});

That's better, and it works, but it's a bit unsightly. It's also somewhat inefficient, because we are waiting for file 1 to be fully read before even asking the operating system to fetch file 2 from disk. This is wasteful, since there's a good chance the OS could work on both files at least somewhat in parallel. Another possible approach is as follows:

const fs = require('fs');

let file1 = null;

let file2 = null;

fs.readFile('file-1.txt', 'utf8', (err, f1) => {

// Error handling omitted for readability

file1 = f1;

if (file2) {

combined = append(file1, file2);

}

});

fs.readFile('file-2.txt', 'utf8', (err, f2) => {

// Error handling omitted for readability

file2 = f2;

if (file1) {

combined = append(file1, file2);

}

});

Now we call readFile for file-1.txt, and when it (immediately) returns we call readFile again - for file-2.txt. Depending on their relative size, either one could finish first, we have no way of really knowing for sure (it's even possible for the larger one to finish first - the OS is unpredictable). To deal with this, we check to see if the opposite file has already completed in each of the handlers. The first callback to execute will find that the other has not, and just return after setting the corresponding file variable. The second callback invoked will find the first has already been set, and will complete the operation.

This is an example of executing asynchronous operations in parallel. There are more elegant ways of doing this, using libraries that model parallel tasks - but we'll cover them later in the chapter.

While the above demonstrates two tasks being done in parallel, where a final task is done with both inputs - what about tasks that must be accomplished in series.

Let's review another example - this time imagining we are working with a database. Retrieving data from a database is the focus of on of the next chapters, for now let's just agree that it's an I/O call. Let's imaging we have variables stored in our database - A, B, C, and D. We want to fetch A first. If A is odd, we want to fetch C, and if A is even we want to fetch B. We then add A to whatever the second parameter was (B or C), and multiply it by D.

We have a sequence, we need A before we can fetch B or C (unless we wastefully fetch both B and C). We can then fetch D, or theoretically we can fetch D in parallel. The chain of dependencies, just with 4 variables, is a mouthful!

In a blocking style program, this would be easy:

a = db.fetch('a');

op = 0;

if (a % 2 == 0) {

op = db.fetch('b');

}

else {

op = db.fetch('c');

}

d = db.fetch('d');

result = (a + op) * d;

In an asynchronous world, here's how we might do this:

db.fetch('a', (err1, v1) => {

if (err1 ) {

console.error(err1);

return;

}

if (v1 % 2 === 0) {

db.fetch('b', (err2, v2) => {

if (err2 ) {

console.error(err2);

return;

}

db.fetch('d', (err3, v3) => {

if (err3 ) {

console.error(err3);

return;

}

console.log((v1 + v2) * d);

})

})

}

else {

db.fetch('c', (err2, v2) => {

if (err2 ) {

console.error(err2);

return;

}

db.fetch('d', (err3, v3) => {

if (err3 ) {

console.error(err3);

return;

}

console.log((v1 + v2) * d);

})

})

}

}

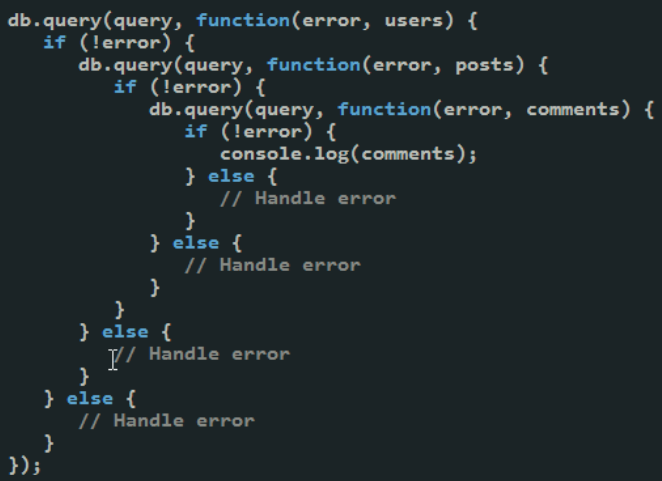

That's clearly a nightmare. You can be more clever, and rearrange things to limit some repetition, but not a lot. Unfortunately, even with some improvements, this still isn't scalable. If we need to make a sequence of calls, where each call needs the result of the previous, this nesting of callbacks, with err handling, cascades. It's referred to as callback hell.

Callback cascading and nesting occurs when we are dealing with the result type of callback - where we are expecting a specific result from an asynchronous call. When results depend on other results, we will continue to find ourselves in this situation. For the first half a decade or so of Node.js, this problem was met with a bit of a shrug. People tried to re-order their asynchronous calls to avoid these structures, and they worked hard to do things in parallel when they could. While the community encouraged developers to avoid the results cascade by doing things in parallel, the community also recognized that the callback approach was indeed inadequate for large programs.

In response, there was an effort to create additional libraries and tooling to help. The first problem identified with callbacks was that while the convention of having err passed as the first parameter and the actual result passed as the second, it was just that - a convention. It was up to the programmer to use the convention - and not everyone did. Moreover, passing errors and data into function couples error handling with the happy path, meaning every callback had to branch for possible errors.

The first solution to the problems above was to create a stronger standard, that modelled callbacks more accurately and helped promote de-coupling of error handling and results processing. This solution was community driven, but eventually made its way into JavaScript itself (and thus Node.js). It's called promises.