Inline Elements, Text, and Links

In the previous section we examined <strong> and <em> as inline elements that hinted at some meaning behind the text they enclosed. Strong words feel like they should be in bold, although it's debatable whether or not emphasis is really saying italics, or whether it's really different than strong. That aside, there are a few inline elements that do convey pretty specific meaning.

Inline elements cannot contain block elements, but they may contain other inline elements. Otherwise, inline elements will typically contain just text. Inline elements, just like block elements, can have attributes.

BTW, you can play along. If you downloaded the html-serve folder, you can run the program on your machine (node server.js). This will start the web browser and you can use the links provided within the text to explore further.

Inline Sizing

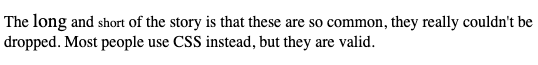

While it's not really in line with pure semantic meaning, HTML does continue to support a small set of sizing elements that are inline. They aren't terrifically supported. At the time of this writing, small has no effect on the text rendered by Firefox. Expect this to continue, as

<p>

The <big>long</big> and <small>short</small> of the story is

that these are so common, they really couldn't be dropped.

Most people use CSS instead, but they are valid.

</p>

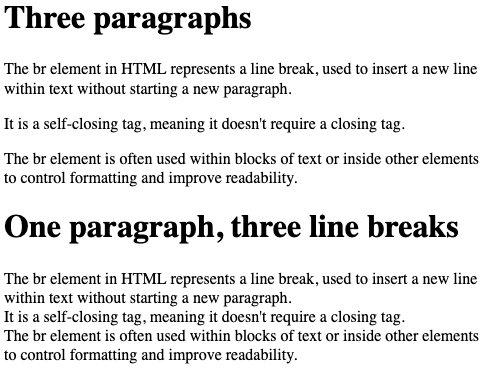

Vertical Spacing

We already saw the br element. It is an example of an HTML empty element, meaning it is both an opening and closing tag, with no content. It is illegal to include any content in the br element in fact (if you think about it, that wouldn't make any sense). The <br/> element causes a single line break. There is no additional vertical spacing/padding applied, the text simply begins on the next line. Contrast this with paragraphs, which by default will also receive some separation spacing.

<h1>Three paragraphs</h1>

<p>The br element in HTML represents a line break, used to insert a new line within text without starting a new paragraph.</p>

<p>It is a self-closing tag, meaning it doesn't require a closing tag. </p>

<p>The br element is often used within blocks of text or inside other elements to control formatting and improve readability.</p>

<h1>One paragraph, three line breaks</h1>

<p>The br element in HTML represents a line break, used to insert a new line within text without starting a new paragraph. <br/>It is a self-closing tag, meaning it doesn't require a closing tag. <br/>The br element is often used within blocks of text or inside other elements to control formatting and improve readability.

</p>

Notice that depending on line wrapping and screen size, the text with line break may have more than three lines - including a few really short lines. This is illustrative of why you want to use caution relying on the br element too much.

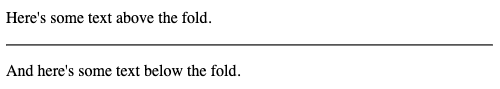

Often we wish to draw a clear separation between two areas of text. On printed paper, this is usually accomplished with a simple horizontal line - and HTML provides this with another empty or self-closing element - <hr/>. The horizontal rule draws a horizontal line on the next vertical space (technically, it is a block element).

<p>Here's some text above the fold.</p>

<hr />

<p>And here's some text below the fold.</p>

Association Elements

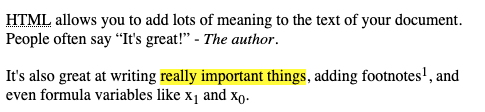

There are inline elements that work to associate text with other parts of the document, or to call them out from the rest in some way. You would be familiar with them from writing any large document, especially technical documentation.

cite- Used for citations, generally will show the text in italics.mark- Wrap text to highlight or mark in some way. In most browsers, the text enclosed in this element will be highlighted in yellow.label- Used to associate text with something else on the page. The label element supports theforattribute, which allows you to specify which element the label is for. This is common on HTML forms, which we will cover in a later chapter.q- Surrounding text with thequoteelement will automatically put quotes around the text. This is very helpful, especially for character encoding issues. It also convey a lot more meaning than just using the " marks within plain text.abbr- Theabbrelement uses thetitleattribute to show a popover when the abbreviation text is hovered over. It can also be used for screen readers to prompt the system to audibly explaint the abbreviation. For example, `WHO semantically associates the World Health Organization with the acronym WHO, in a meaningful way.subandsup- These are for subscripts and superscripts.time- Wraps a time value, in hopes of allowing the browser to display the time value in a local-specific way. In practice, most browsers don't do a whole lot with this, but it's nice to use when possible to take advantage of any features the browser can provide. Thetimeelement also supports adatetimeattributes that expects a valid timestamp (in an ISO formatted string). This can be useful to associate text (ie. Independence Day) with a specific date (2027-07-04).

<p>

<abbr title="HyperText Markup Language">HTML</abbr> allows you

to add lots of meaning to the text of your document. People often

say <q>It's great!</q> - <cite>The author</cite>.

</p>

<p>

It's also great at writing <mark>really important things</mark>,

adding footnotes<sup>1</sup>, and even formula variables like x<sub>1</sub>

and x<sub>0</sub>.

</p>

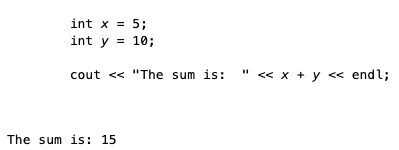

Code / Computer Output

It's somewhat questionable whether all of the inline elements we've added to HTML for computer code was a great idea, it seems sort of biased to a particular domain (people who write about code), but hey - why not. Your results may vary, depending on your browser - there isn't a lot of agreement between browsers how code should be rendered. Firefox in 2024 renders variable names in italics, for example. There's no question that the element convey meaning, but they don't really dictate visual representation

<pre><code>

int <var>x</var> = 5;

int <var>y</var> = 10;

cout << "The sum is: " << <var>x</var> + <var>y</var> << endl;

</code>

</pre>

<samp>

The sum is: 15

</samp>

There are additional inline elements, and lots of resources on the web that gives more explanation.

WWW Schools has a good listing of inline elements, and allows you to demo some of them online. We are going to return to some more soon, including the a element below, and the img element when we cover multimedia. First. let's take a look at some other text issues that come into play with HTML.

Text & Special Characters

When we talk about inline elements, we are mostly talking about text, and so this is a good enough place as any to discuss some of the quirks about text, as it appears in HTML. We've already seen that text in HTML uses white space collapsing - meaning multiple consecutive spaces, tabs, and even new lines are always rendered as a single space. This is one instance, but not the only instance, where the text that you write in your editor is not the same as the text that appears on the browser screen once the HTML is rendered.

HTML is of course a programming language, and so there are special characters in the language itself that act as delimiters. As any language, HTML must be parsed by machine code (the browser, in most cases), and therefore there needs to be some provisions for differentiating between delimiters and true characters.

In HTML, the most noticeable delimiters are the < and > that make up the opening and closing tags - <body>...</body>. This angle brackets may not appear within text contents, as they create ambiguity for the parser:

<p>

It is against the language rules to have < or > in the text, like was done here!

</p>

The above HTML may or may not render at all, browsers still have discretion when dealing with invalid HTML. Make no mistake, however - it is invalid HTML.

HTML defines a number of named entity references, which are essentially like the escape codes you use in other languages (for example, the \n as a new line). For the angle characters, we have > for the greater than symbol, and < for the less than symbol. There are also named entities for <= and >=.

| Char | Named entity |

|---|---|

< | < |

<= | ≤ |

> | > |

>= | ≥ |

There are additional characters that are not permitted to be within text content of HTML elements. Not unexpectedly, the & that begins an entity reference is a special character - and as such must be written with a named entity reference itself - &. There are also named entities for character that often create confusion when copy and paste is used between editors, especially when the editors are using different character encodings. A prime example of this is the double quote character - ". When using rich text editors, often the quotes are different from the ASCII quote, which will not work well in HTML. Due to the possible confusion, it is always recommended to either use the <q> element to wrap text that should be put in quotes, or to use the corresponding entity reference - ".

Here's a listing of some of the more commonly used entity references. Each named entity reference can also be written using it's hex or decimal code (although to most people, this is less readable) There are many, many more.. There are even entity references for emoji 😜

| Character | Named Entity | Hex | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|

| < | < | &x0003C; | &x60; |

| ≤ | ≤ | &x2264; | &x8804; |

| > | > | &x0003E; | &x62; |

| ≥ | ≥ | &x02265; | &x8805; |

| " | " | &x00022; | &x34; |

| ‐ | ‐ | &x2010; | ‐ |

| ˙ | ˙ | &x002D9; | ˙ |

| · | · | &x000B7; | · |

Comments

If you look in your developer tools when loading a web page, or right click and choose "View Source", you can always see the HTML loaded in the browser. It's source code, and just like any other source code, it may or may not have comments. You of course know what comments are all about - as a programmer you hopefully comment your code to the extent that is necessary for some other poor soul (or your future self) to understand what you've done.

HTML is no different, however since HTML is typical not complex, most of the time comments are used for more routine purposes - like author names, or additional information about the page.

Comments in HTML are delimited by <!-- and -->. There are no single line comments (like the // vs /* */ in some other languages).

<p>

Here's some text.

<!--

This is a comment, and won't render

-->

Here's some more text.

</p>

<!-- This won't render either-->

Use comments in HTML sparingly. There really shouldn't be a need to document your HTML - if it's complex enough to confuse someone, something has gone terribly wrong. Remember, comments actually are part of the HTML that gets sent to the client - therefore it takes up network bytes.

Pro Tip💡 Unlike in other programming languages, your end users have direct access to your source code. Possibly more than any other language, HTML is very much open, there is literally no way your web page can render in someone's browser while at the same time preventing them from seeing the HTML code if they want to. Why is this important? Your comments are part of your code. Keep your comments professional. Do not put anything in comments that you don't want the entire world to see. This includes unprofessional language, but it also includes secrets (API keys, etc.). Remember, HTML code that you write can be seen easily by anyone who can load the web page.

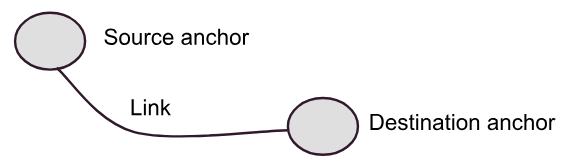

Links and Anchors - HyperText!

We've saved the best inline element for last, the anchor element. It's the best because it puts the hyper into HyperText. Anchor elements are the links that we take for granted on the web. The term "link" though isn't really used the same way it was thought of (in theory) when HTML was created. Instead, links were the path between two anchors - a source and a destination.

In HTML, there are implicit anchors - such as a URL, and explicit anchors created with <a> elements. Typically, we create source anchors within web pages, which identify destinations by using a URL. The following creates a text link to Mozilla.org:

<!doctype html>

<html>

<body>

<p>Here's a <a href="https://www.mozilla.org">link</a>

to a great place to get a web browser</p>

</body>

</html>

In the source code above, the <a> element is a source anchor - it's a jumping off point, to another hypertext. The href attribute is indicating that the destination is on another page, at a different domain - https://www.mozilla.org. The URL itself is an implicit anchor. We know, of course, that the browser renders the <a> element as a link. Links are usually rendered as colored text, with an underline. The color of the text is usually blue, and the underline is usually removed when the link is clicked. This is the default behavior of the browser, and can be changed with CSS.

The value of the the href attribute is a URL. The URL can be a relative URL, or an absolute URL. If the URL is relative, it is relative to the current page. If the URL is absolute, it is a full URL - which must begin with the scheme.

Let's assume you have an HTML page loaded from https://www.example.com/foo/bar.html. The following href values are all valid:

href="baz.html"- this is a relative URL, and the browser will requesthttps://www.example.com/foo/baz.htmlhref="/baz.html"- this is a relative URL, and the browser will requesthttps://www.example.com/baz.htmlhref="https://www.anotherexample.com/baz.html"- this is an absolute URL, and the browser will requesthttps://www.anotherexample.com/baz.htmlhref="//www.anotherexample.com/baz.html"- this is an absolute URL, and the browser will requesthttps://www.anotherexample.com/baz.html. Thehttpsis assumed, based on the fact that you are currently viewing anhttpspage.

The following are problematic, and need to be avoided:

href=www.anotherexample.com/baz.html- this is a relative URL, and the browser will requesthttps://www.example.com/foo/www.anotherexample.com/baz.html. Clearly, that's unlikely to be what you actually wanted - but without the scheme, or leading//, the browser will assume it's a relative URL.href="http://www.anotherexample.com/baz.html"- This is an absolute reference, and is ok. However, you should note that linking tohttpsites within anhttpssite might invoke a warning from the browser when the user clicks it. Sometimes we have no choice, the site we link to is only served withhttp, but generally if you can, always choosehttps.

Browsers respond to clicking on source links with href values by generating a new HTTP GET request to the target URL.

Anchors within pages

As discussed above, there are two anchors - a source and a destination. In the examples above, we were linking to a URL, which implicitly is an anchor. We can create explicit destination anchors within an HTML page as well though.

The following page creates several explicit anchors, and links to them at the top.

<!doctype html>

<html>

<body>

<!-- Source Anchors -->

<p>

<a href="#section1">Section 1</a>

<a href="#section2">Section 2</a>

<a href="#section3">Section 3</a>

</p>

<!-- Destination Anchors -->

<h1><a name="section1">Section 1</a></h1>

<p>This is section 1</p>

<h1><a name="section2">Section 2</a></h1>

<p>This is section 2</p>

<h1><a name="section3">Section 3</a></h1>

<p>This is section 2</p>

</body>

</html>

Try this one on your own machine, but make the window really small, so you can't see the entire vertical page. When you click on the section links along the top of the page, the browser responds by scrolling down to the location of the destination anchor. The destination anchors are <a> elements, but instead of having a href attribute, they have a name attribute. The name attribute is the destination anchor. The browser will scroll the page to the location of the destination anchor when the source anchor is clicked.

Notice that the source anchors still use href - they are sources, and the href creates the link to the destination anchor. In this case, the source anchors are referring to the current page, but at the named destination - prefixed with #. We can also combine a URL and a name to create links to different web pages, at specific locations. For example, if the html with the three section links were to be hosted at https://my-anchors.com/sections.html, the following would link to the second section:

<a href="https://my-anchors.com/sections.html#section2">Section 2</a>

Relative vs Absolute URLs

When linking to other resources that are external to our own site (on a different domain), we have no choice but to list URLs using the full absolute syntax. If our site is hosted on https://mysite.com and we are linking to something on https://example.com, then the href must be absolute. What about when we are linking to resources on our own site? Should we use relative or absolute URLs? In almost all cases we want to link using relative links. This is because relative links are more robust - they are less likely to break when the site is moved, or when the site is accessed from a different domain. If you use absolute URLs, and the site is moved, then all the links will be broken. If you use relative URLs, then the links will continue to work, as long as the relative structure of the site is maintained. This also lets you develop your web site on your own computer, using a localhost web server, and have it function exactly the same way it will when it's deployed to a real server.

Sometimes, within a web application with many pages, with a nested structure, it can feel awkward to restrict yourself to relative links - you find yourself using .../.../other.html type syntax, counting the ../ up complex paths. In this case, remember that an href value of /other.html is still a "relative" link, in that it is not changing the domain - it's just linking to a resource starting at the root, rather than the current path. This can be a good compromise, it let's you link directly to a resource within your site from anywhere within your site using the same URL - but it does not break if the site is moved to a different domain.

Relative paths in href that do not start with the / root character are always evaluated relative to the current page - with one caveat. It is possible to include a <base> tag in the <head> of the document, which will change the base URL for all relative links. This is rarely used, but can be useful in some cases. Use this with care however, as it does make the HTML harder to understand.

Anchor Targets

Often when we link to a new page, we want to open the new page within a new browser window or tab. This is done using the target attribute of the <a> tag. The target attribute can take several values, but the most common are _blank and _self. _blank will open the link in a new tab or window, while _self will open the link in the current tab or window. The default is _self, so if you don't specify a target, the link will open in the current tab or window. A third possible target is _parent, which can be used to open the link in a parent window, when the current window is a frame within the parent (we'll discuss frames later).

<a href="https://www.example.com" target="_blank">Open in new tab</a>

<a href="https://www.example.com" target="_self">Open in current tab</a>

Generally opt for keeping _self when you are linking within your own site. It's up to you whether to use _blank or not when linking to external sites. You might prefer to keep your own page open on the users browser, while they have the option to read the newly opened tab. Remember however that most people's browsers let them decide, so your choice of target is just a suggestion to the browser and the user.